In our special theory of relativity (STR), time dilates for physical systems in uniform motion relative to observers. For instance, if a physical system is moving at 0.8 the speed of light relative to us, we observe it changing state at 0.6 the rate we change state, and if the system is a starship with a clock onboard, we measure that clock ticking 36 times for our clock’s 60 ticks. In STR, this phenomenon is called time dilation, and it has been confirmed by a wealth of empirical data going back to Rossi-Hall (1940) and Frisch-Smith (1962). The standard explanation, based on Einstein’s two postulates, is regarded as non-classical.

What if there were also a simple, even classical, kinematic explanation of our time dilation measurements? What if it could be shown that decreases in the rate at which systems change intrinsically follow for purely kinematic reasons from a single postulate? Here begins a presentation of the isotacheian model in the form of videos, 3D models, and documents. This presentation and the playlist are currently under construction.

Find my recently published article on this model here.

Here is a playlist of four short videos, each under five minutes, explaining the isotacheian model.

Dynamic Models

Unfortunately, these models do not perform especially well on some smartphones.

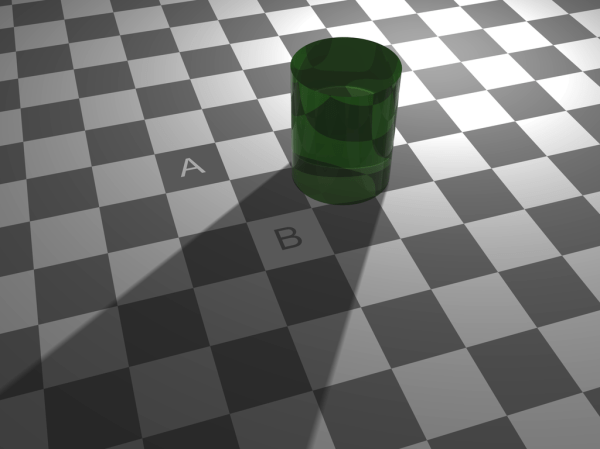

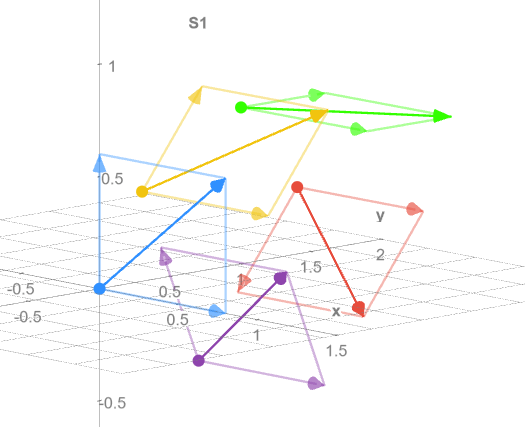

- Five Particles Set v to any value in the range [0,1] to see the Pythagorean relation between an isotacheian system’s speed in R and the rate at which its particles can move relative to each other and thus the rate at which it can change intrinsic state.

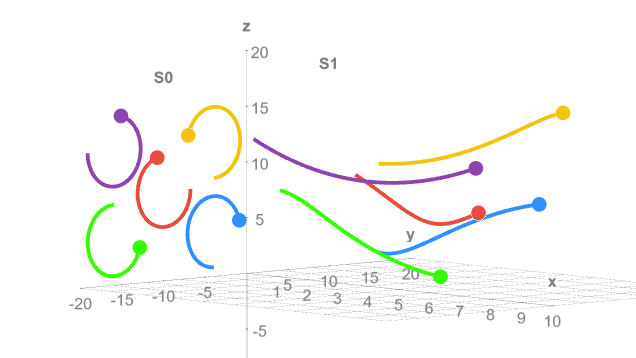

- Helical Paths Set v to any value in the range [0,1] to see how the rate of intrinsic change for S1 compares to that rate for S0, which is at rest in frame R. The isotacheian model does not require helical paths to work, but they can make the Pythagorean-Lorentzian relation intuitive, and they have some justification in physics.

Briefly…

Commentary

Here, I will elaborate on questions raised, points needing clarification, and potential problems and objections.

- What are s-particles?

- The isotacheian model permits but does not require an aether. (Coming soon.)

- Vector Analysis vs. Vector Addition (Coming soon.)

- (More planned.)

Other Sources

In recent years, I have discovered some fellow isotacheians whom I name in the introductory video. Here are some links to them and their work.

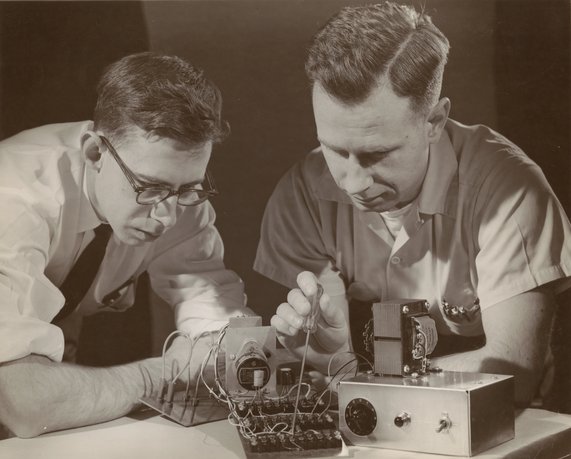

- Albrecht Giese (PhD Physics) on time dilation as a consequence of particles oscillating permanently at the speed of light.

- Federico Giudiceandrea (MS Engineering) on how Lorentz time dilation follows directly from Epicurean atomism. (Written in Italian)

- Robert A. Close (PhD Physics) presenting a classical account of STR in which material objects are composed of waves in an aether. His book is The Wave Basis of Special Relativity.

- Chantal Roth (PhD Scientific Programing) demonstrating how Lorentz results can be obtained from a model in which material objects are composed of waves in an aether.